Climatic conundrum

a recent research suggests that greenhouse heating would cause warmer, wetter air to reach Antarctica, where it would deposit its moisture as snow. Therefore, contrary to the presumed collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet, computer models are showing that the great mass of ice in the Antarctic could grow, causing sea level to drop as water removed from the sea became locked up in continental ice. Some other observations have also steered the opinion of many scientists working in Antarctica away from the notion that sudden melting there might push sea level upward several metres sometime in the foreseeable future. For example, glaciologists now realise that out of the five major ice streams feeding the Ross Sea, one of the largest had stopped moving about 130 years ago, perhaps because it lost lubrication at its base.

a recent research suggests that greenhouse heating would cause warmer, wetter air to reach Antarctica, where it would deposit its moisture as snow. Therefore, contrary to the presumed collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet, computer models are showing that the great mass of ice in the Antarctic could grow, causing sea level to drop as water removed from the sea became locked up in continental ice. Some other observations have also steered the opinion of many scientists working in Antarctica away from the notion that sudden melting there might push sea level upward several metres sometime in the foreseeable future. For example, glaciologists now realise that out of the five major ice streams feeding the Ross Sea, one of the largest had stopped moving about 130 years ago, perhaps because it lost lubrication at its base.

One of the major concerns for environmental scientists has been the increase in sea level due to heating of the earth's surface. Most experts deem it as an inevitable consequence of the mounting abundance of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping 'greenhouse gases' in the air.

More than 20 years ago, some scientists had warned that global warming might cause a precariously placed store of frozen water in Antarctica to melt, leading to a calamitous rise in sea level, about five or six metres. Scientists of various disciplines are attempting to gather answers using a variety of experimental approaches, ranging from drilling into the Antarctic ice cap to bouncing radar off the ocean from space.

J H Mercer of Ohio State University, in the us, was one of the first prominent geologists to raise concern that global warming might trigger a catastrophic collapse of the Antarctic ice cap (Scientific American, Vol 276, No 3).

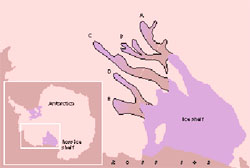

A group of American investigators had organised a coordinated research programme in 1990 called 'Sea rise ' (for Sea-level Response to Ice Sheet Evolution). The report of their first workshop noted the presence of five active ice streams drawing ice from the interior of West Antarctica into the nearby Ross Sea. They noted that these ice channels might be manifestations of collapse already under way.

In fact, the relation between climate warming and the movement of West Antarctic ice streams has become increasingly tenuous. According to the measurements of Ellen Mosley Thompson of the Ohio State University Byrd Polar Research Center the measurements of the rate of snow accumulation near the South Pole show that snowfalls have mounted substantially in recent decades, a period in which global temperature has inched up; observations at other sites in Antarctica have yielded similar results. But the places in Antarctica being monitored in this way are few and far between, Mosley-Thompson emphasises. Although many scientists accept that human activities have contributed to global warming, no one can say with assurance whether the Antarctic ice cap is growing or shrinking in response.

In just a few years the uncertainty could disappear if the National Aeronautics and Space Administration is successful in its plans to launch a satellite designed to map changes in the elevation of the polar ice caps with extraordinary accuracy - perhaps to within a centimetre a year. Until this and other projects are completed, scientists trying to understand sea level and predict changes for the next century can make only educated guesses.

Whatever the fate of the polar ice caps may be, most researchers agree that sea level is currently rising. The difficulty has been in establishing the fact. Although tide gauges in ports around the world have been measuring sea level for many decades, calculating the change in the overall height of the ocean is a surprisingly complicated affair. The basic problem is that land to which these gauges are attached can itself be moving up or down. One can, in principle, determine the true rise in sea level by throwing out the results from tide gauges located where landmasses are shifting. But the strategy rapidly eliminates most of the available data.

Geophysicists have devised clever ways to overcome some of these problems. One method is to compute the motions expected from post-glacial rebound and subtract them from the tide gauge measurements. Using this approach, William R Peltier and A M Tushingham from the University of Toronto, found that global sea level has been rising at a rate of about two millimetres a year over the past few decades.