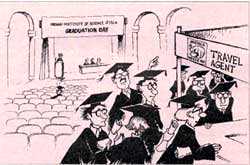

Brain drain backs up

A RS 10-crore aid package from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to help involve Indian expatriate scientists in leading areas of research has buoyed the sagging spirits of science administrators faced with the exodus of Indian scientists to greener pastures abroad. The aid comes in the wake of a proposal seeking to create permanent jobs for research scientists in a desperate move to stanch the brain drain. The proposal indicates a turnaround in the truncated philosophies guiding scientific research in India, content with increasing funding while ignoring sociological aspects.

A RS 10-crore aid package from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to help involve Indian expatriate scientists in leading areas of research has buoyed the sagging spirits of science administrators faced with the exodus of Indian scientists to greener pastures abroad. The aid comes in the wake of a proposal seeking to create permanent jobs for research scientists in a desperate move to stanch the brain drain. The proposal indicates a turnaround in the truncated philosophies guiding scientific research in India, content with increasing funding while ignoring sociological aspects.

The aid follows a study by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), which estimated that the turn of the century would have 540,000 Indian scientists and technicians working abroad.

The study says that the slow pace of economic reforms has resulted in a stagnant demand for research scientists in the industrial sector. Complicating the situation is the grim fact of the "internal brain drain", which has the number of postgraduates in science declining and highly-educated scientific personnel migrating to other professions.

Ashok Jain, director of the National Institute of Science, Technology and Development Studies (NISTADS) is afraid that "if corrective measures are not initiated immediately, research organisations like the CSIR may become absolutely ineffective".

Even recent proposals to hike royalties and salaries for research scientists have failed to make an impact yet. The study carried out by NISTADS covering 6 leading scientific institutes reveals that despite allocations for more and more specialised areas of research, the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore, for instance, lost 27 of the 51 doctorates trained at its molecular biophysics unit from 1974-84. In its solid state and structural chemistry unit, 32 out of the 44 PhDs who trained between 1980-89 are now serving abroad.

High level migration Data collected from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), Bombay, the National Chemical Laboratory (NCL), Pune, the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL), Ahmedabad, the Indian Institute of Chemical Biology (IICB), and the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS), Calcutta, indicate similar trends. Various earlier studies have already noted the high levels of migration from the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) -- 33.7 per cent of students who graduated from the IIT, Madras, in 1983-87 migrated to foreign countries.

The annual brain drain statistics are estimated to be between 5,500-6,500, of which about 90 per cent head for the United States. Of the total workforce abroad today, 30 per cent is in the US, 23 per cent in West Asia and 11 per cent in Western Europe. The study reveals that the economic gain to rich countries through the inflow of scientific and technical personnel from poorer nations far exceeds the aid funnelled by them. Rough calculations pegged the losses at US$ 10-20 billion between 1966-86 due to the migration of 21,094 engineers from India to the US alone, while the aid the US extended was well below this figure, estimated.

Says Dinesh Abrol, senior scientist, NISTADS, "With all indications that the intellectual and economic loss of science is going to continue and, in fact, speed up, there is need to take a new look at stemming the outflow." At the same time, scientists like B V Reddi, general secretary of the CSIR Scientific Workers' Association (SWA), feel that efforts should focus on developing and absorbing the existing brain bank in the country. They are ranged against expending effort to attract Indian scientists working in foreign countries.

Says Jain, "Research scientists were offered short-term assignments with fellowships. But over the years, it has been seen that these incentives are not enough to make them stay. This is why proposals for permanent posts are now being mooted."

In 1980, trying to attract Indian scientists from abroad, the UNDP-funded Transfer of Knowledge Through Expatriate Nationals (TOKTEN) was instituted by the CSIR. Highly placed Indian expatriate scientists are invited for projects of 6-12 weeks duration in both private and public sector industries and research institutes. Till 1993, 450 experts were placed in 250 institutes. The UNDP has already provided Rs 90 lakhs for the programme. Following its recent evaluation of the programme, the CSIR and the department of company affairs, the UNDP has allocated another Rs 75 lakhs for 6 years.

Abrol points out that plucking out senior expatriate scientists and giving them director-level posts in the CSIR has been singularly unsuccessful. "Each one of the handful of such directors soon went back, unable to comprehend that the vast powers available to heads of institutes can only be exercised if legitimacy is given by their colleagues," he says. Thus R C Singal, appointed director of the CBRI in 1992, returned to the US in 10 months; S K Lahiri, deputy director between 1986-88, eventually returned to the US; and R Krishna, appointed director of Indian Institute of Petroleum, Dehradun, in the late '80s quit, his post in a cloud of controversy.

Science administrators are pressing for new permanent jobs but without much hope. Under current governmental policies, the creation of new posts is next to impossible. Says Jain, "The human resources development ministry cannot create more jobs; the department of science and technology is not mandated to do so; and the CSIR is paralysed by a ban on fresh recruitments."

In addition, the Scientists' Pool Scheme launched in 1958, offers temporary placements for a maximum of 3 years to highly qualified Indian scientists, engineers, technologists and medical personnel returning from abroad. Paid between Rs 2,500-6,300 per month, "pool officers" are placed in government-funded organisations. The scheme was later also thrown open to qualified scientists graduating from Indian universities. About 9,000 scientists have so far been placed.

Reddy, however, says that the steadily declining number of people availing of the scheme -- 333 persons employed as pool officers in 1988, dwindling to 77 in 1992 -- indicates that such short-term programmes are no longer of any value. He is also sceptical of TOKTEN's value: "The high level experts invited under this programme are generally misfits for ongoing projects in the country. Moreover, these experts are keener to visit India on a 'paid holiday' in order to meet their families. Not only are they less interested in contributing to a project, there is no system of accountability for them either." Jain says that TOKTEN and the Scientists' Pool Scheme do not create new constituencies of research that can help to absorb more people.

Plugging the drain

This is why hopes are now pinned on economic reforms. N R Rajagopal, heading the CSIR's human resource development group, feels that economic liberalisation will soon plug the brain drain, as the demand for research scientists shoots up with the arrival of state-of-the-art technologies. He points out that institutes such as the National Aerospace Laboratories, Bangalore, have bagged contracts from British and Russian air authorities to conduct high-level aeronautical research.

But not many scientists concur with Rajagopal. Reddi says, "In the age of liberalisation and with foreign products flooding the market, the term 'brain drain' itself is outdated. Instead of developing our own research capabilities and products, we have simply decided to give in to foreign competitors." Multinational corporations entering India are keener on establishing a market base for quick returns rather than initiating long-term R&D programmes.

In fact, the NISTADS study found that while research facilities in several frontier areas of science have been set up in government-funded institutes, the key factor, other than the economic incentive, responsible for emigration is the isolation of scientists working in highly specialised disciplines. Due to the absence of linkages between splinter groups of scientists working in specialised areas, the requisite intellectual climate is hazy and cold.