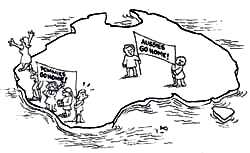

Whose land is it, anyway?

A PROPOSED Australian law that allows aborigines to claim land has been criticised by the country's business community, which fears it could curb mining. The proposed native land-title legislation arose from a 1992 high court ruling that recognised the native title to land under the country's common law.

A PROPOSED Australian law that allows aborigines to claim land has been criticised by the country's business community, which fears it could curb mining. The proposed native land-title legislation arose from a 1992 high court ruling that recognised the native title to land under the country's common law.

The ruling, known as the Mabo judgement after one of the plaintiffs, rejected the traditional doctrine that Australia was terra nullius (belonged to no one) when Britain first colonised it in 1770.

Native Australians have only recently gone on the offensive to undo past injustices. The late Eddie Mabo of the Meriam tribe, which inhabits the Murray Islands in the Torres Strait north of Queensland, initiated proceedings in 1982 against the Queensland government. This resulted in the decision that the Meriam people hold native title over the Murray Islands. In its wake, mainland aboriginal groups have filed suits to assert land ownership.

The bill recognises and protects native titles to land and sets up a court to deal with claims. It establishes a means to award compensation where the title has been extinguished or impaired by the validation of existing interests in land. However, native title claims can be made only for land the government has not sold or leased. According to one estimate, the proposed federal legislation potentially affects 92 per cent of Australia's land mass.

Australian prime minister Paul Keating said, "In general, the bill provides that governments (of states and territories) can confirm any existing ownership of natural resources, including forests and minerals."

The decision attempts to balance the desire for economic development from miners and farmers with demands for justice for indigenous aborigines. It may also help Australia shed its image as a racist nation where aborigines are treated as second-class citizens.

The federal legislation has won support from seven of the country's eight state and territory governments. Western Australia, which has the largest area that may be claimed under native titles, stands alone against the proposal and plans to go ahead with a provincial legislation that recognises only the "right of traditional use". The proposed federal law will, nevertheless, override the provincial legislation.

Support for the legislation has come from the National Farmers' Federation, which said the bill satisfies most of the farm sector's concerns. "We believe our primary objectives have been achieved," said federation president Graham Blight.

Effect on industry However, crticism from the Business Council of Australia (BCA) has fuelled concerns about the law's impact on industries, especially mining, because minerals are the country's biggest export income earner. BCA said the legislation "will act as a significant brake on mining investment...with adverse consequences for our future economic development".

BCA executive director Paul Barratt said the legislation is "unnecessarily complex and will lead to uncertainty and frustration, which will militate" against long-term mining investments. A major joint venture mining project with Japan to develop zinc and lead deposits is bogged down because of compensation claims.

The political implications of this ruling are still being debated. But the questions about the legality of existing mines -- especially diamond mines -- have already caused a flutter in diamond markets worldwide.

If mining rights pass on to the aborigines, it could create complications for companies such as De Beers, whose Diamond Trading Company and its affiliate, the Central Selling Organisation (CSO) would have to renegotiate purchase rights over rough diamonds found in the Argyle and Kimberley mines in Australia.

As a result of the claims made by the aborigines, supply of diamonds that are mostly cut and polished in India could be help back, affecting the Indian diamond trade. Indian diamond merchants already face a planned cut in supply by CSO because of excessive stocks in the India specialises in. It will take at least six months for things to return to normal, according to sources in CSO.