Catastrophe!

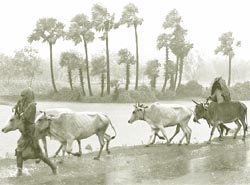

the coast of Orissa is today a picture of death and devastation. The super cyclone that hit the state's 10 coastal districts on the morning of October 29 remained centred there for about eight hours, with wind velocities rising to nearly 300 km/h for almost four hours. Swept by the ferocious winds, the sea ingressed 15-20 km into the land with 9-metre-high waves. The trail of death and devastation left behind has no parallel in the country in the past century.

the coast of Orissa is today a picture of death and devastation. The super cyclone that hit the state's 10 coastal districts on the morning of October 29 remained centred there for about eight hours, with wind velocities rising to nearly 300 km/h for almost four hours. Swept by the ferocious winds, the sea ingressed 15-20 km into the land with 9-metre-high waves. The trail of death and devastation left behind has no parallel in the country in the past century.

Thousands of people are feared to have perished. Although the state government has confirmed only 317 deaths, even officials point out that the figure would be over 5,000, and this excludes the worst affected districts of Kendrapada, Jagatsinghpur and Khurda, which remain inaccessible as we go to press. More than two million houses were washed away and almost 20 million people rendered homeless. One-third of the land area of Orissa lies submerged under seawater and preliminary estimates say that the paddy crop in an area of 1.5 million hectares has been lost. "There is not a single tree left on the landscape,' said Giridhar Gomang, the chief minister of Orissa. Telecommunication links have been snapped and there is no trace of the roads. Even the prime minister's office could not get in touch with the state government by telephone.

"There is no food or drinking water. There are thousands of bodies floating around. We cannot survive for long in this way,' said S K Mahapatra, chairperson of the Paradip port, which has been reduced to rubble. There is already talk of epidemics breaking out. According to the state government, more than 20 people have died of cholera in Bhubaneshwar and Cuttack. "After surviving three days without water, now people are drinking stagnant rainwater in the drains. And eating dead cattle as it comes free,' said Debashis Majhi, a resident of the state capital. "It would take 50 years to rebuild Bhubaneshwar,' said Ram Krishna Das of the state capital who arrived in Delhi on November 3.

The heavy downpour that accompanied the cyclone lashed the region for two days subsequently. And then came in reports of flash floods. After the third day, when the high-velocity winds and the rains had subsided, the Army and the Navy plunged into what some say is the largest relief operation ever undertaken in the country.

More than five thousand Army personnel, ten aircraft and five naval ships battled for the first two days just to clear the roads and the sea route to Paradip to move the relief packages coming in from neighbouring states. People are scattered all over the place in small groups of 5 to 10, making organised relief and rescue all the more difficult. So, when the relief finally arrived after days of waiting, it sparked off riots.

This was Orissa's second brush with the sea's wrath within a fortnight. On October 17, a cyclone struck the Ganjam district, killing 200 people. A warning issued five days before the super cyclone struck was taken lightly. The Indian Meteorological Department ( imd ) officials sighted the cyclone at the Malay coast. Then, the satellite pictures showed it near the Andaman islands. But, at that time, it did not seem capable of such devastation. As it moved northwards, imd declared that it would not hit Orissa but pass through West Bengal. Cyclones are a usual phenomenon at this time of the year in the Bay of Bengal.

It was at this point that the cyclone's characteristics changed. Instead of moving northwards, as predicted, the super cyclone stayed put in the Bay of Bengal. This led to its heating up and finally to its metamorphosis into a super cyclone. Within a few hours, it was wreaking havoc in Orissa.

This yet again brings into focus India's failure at disaster management. While the cabinet secretary called upon the National Crisis Management Group under the ministry of agriculture to supervise what was declared a "national calamity', the defence minister, seemingly unaware of the group's existence, declared that the government would establish such an agency.

R B Singh, convenor of the Disaster Studies Research Group of the Delhi University's department of geography, says changes in the natural vegetation cover, from tall trees to agricultural land, leave the coastal areas vulnerable to greater damage from high-speed wind as the natural wind barriers do not exist. After a cyclone in 1971, the state government initiated extensive plantation of casurina trees on the coast. But its planning was so faulty that now it hampers beach formation.

Related Content

- 2023 disasters in numbers

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding unauthorized and illegal construction of houses, shops and other commercial establishments in Noida and Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, 02/04/2024

- Natural catastrophes in 2023: gearing up for today’s and tomorrow’s weather risks

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding illegal mining and deforestation among others responsible for the natural calamities in Himachal Pradesh, 29/02/2024

- Empowering communities in the face of climate change in Egypt

- Libya: storm and flooding 2023- rapid damage and needs assessment