Poor pay for ecological neglect

LARGE parts of India are again in the grip of drought -- from the dry regions of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Marathwada and Vidarbha to the high rainfall state of Kerala.

LARGE parts of India are again in the grip of drought -- from the dry regions of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Marathwada and Vidarbha to the high rainfall state of Kerala.

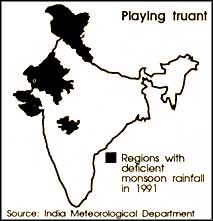

By official meteorological accounts, this was a near normal year. The pundits in New Delhi's Mausam Bhawan have a map of last year's monsoon rainfall. According to it, only a very small part of India had deficient rainfall.

Eastern and western Rajasthan, at 35 per cent below average, as also Saurashtra and Kutch, at 44 per cent less, certainly fared badly. But Kerala had a good summer monsoon -- nearly a fifth above average. Sarguja, which shot into national attention with its starving tribals and a subsequent visit by the Prime Minister, P V Narasimha Rao, had normal rains. So did Vidarbha, with 19 per cent less than average, but still within the 'normal range' stipulated by the India Meteorological Department. In Marathwada, the rains were 23 per cent less -- just four per cent off the lower end of the normal range.

Yet the number of people on the roads looking for jobs, water and fodder to feed themselves and their animals over the last few months has been legion.

Out of 42,000 villages in Maharashtra, nearly 70 per cent in 26 districts are drought-stricken. Some 25,000 villages face drinking water scarcity. Fodder has been in short supply. In Beed district, the worst-affected, there have been distress sales of cattle.

The worst-affected districts of Gujarat are Surendranagar, Broach, Banaskantha and Jamnagar. From Kutch, migration started in October itself when some 10,000 maldharis (shepherds) were forced to move towards Bhavnagar, Kheda and Ahmedabad districts with over a lakh heads of cattle. Tensions soon emerged between the maldharis and the farmers. In recent months, several cases of bhelan (illegal grazing of cattle) and subsequent clashes have been reported. Farmers' organisations in south Gujarat have asked the government to streamline the migration.

Some 30,000 of the 40,000 villages in Rajasthan -- in all the districts except Bundi -- have been affected by drought. In Madhya Pradesh, the drought has affected 18,190 villages in 28 districts. The opposition Congress leaders reported at least 10 starvation deaths which were denied by the state government. In Kerala, 629 of the 1,464 villages lost more than 50 per cent of their winter crops. Water scarcity has been particularly serious in Alapuzha, Idukki and Kottayam districts. The government supplied drinking water through tankers and even boats. People in Kerala do not usually have to walk long distances to reach their water, hence tankers were pressed into service to provide water at the doorsteps.

But why this desperation in a near normal year?

Dry calamity The Maharashtra government claims that it is in the grip of one of the severest droughts the state has seen in the last 20 years. In mid-May, a Central team was rushed to Maharashtra and there are reports that the Prime Minister may go too in early June. For the lakhs of villagers, this summer has undoubtedly been wretched.

This has happened despite the fact that Maharashtra is the only state in India with an extensive safety net -- the Employment Guarantee Scheme -- to help the poor withstand the rigours of drought. The scheme, which started after the bad drought of 1972, was a bold step, promising guaranteed employment -- digging ponds, planting trees, making roads -- within a few kilometres of where a villager lives -- effectively stemming migration and famine. Yet things went wrong this year.

Numerous people did not come to the relief programmes. The possible reasons are complex. The biggest is that EGS does meet many needs. For instance, fodder is acutely short. A bundle of fodder which cost Re 1 touched Rs 6 early this year. Desperation for fodder forced many to migrate to sugarcane areas where labour as well as fodder (sugarcane leaves) is provided. More than 3.5 lakh people from Beed district alone have migrated to sugar factories. But sugar factories pose a double bind. The crop could well have been a singular cause of increased drought as this water- guzzler uses up most of the irrigation in the state. The crop which is grown on just 2.6 per cent of the cultivated land -- up from 0.8 per cent in 1960-61 -- consumes a staggering 60 per cent of the state's water. With bumper outputs, last year the state ranked fifth in the world. This year, 38 more sugar cooperatives have been sanctioned, drought or no drought.

M D Sathe, a Pune - based economist who has studied the scheme extensively believes that EGS can go beyond providing daily wages during distress periods, and even provide fodder, but only if village communities are given a strong stake in the management of village natural resources. EGS money helps to build assets like wells, tanks and trees. But there is no structure to take care of these. Ponds soon silt up and saplings die.

Two years ago, a new theme was added to the employment guarantee concept of EGS called 'mobilising local manpower for village development' -- an attempt at village-planning based on watershed development using local labour. Villagers would plan for their village environment and EGS would be used to mobilise the labour. It is a scheme that could make Maharashtra extremely drought-resilient. But, surprisingly, this scheme is in the process of getting slashed. Says Sathe, "the government has been given wrong information by political parties that the villagers are not agreeing to it. On the contrary, Sathe himself has found a favourable response in the villages he has visited. But building up the rural environment is not a priority for the state's politicians.

Survival foods

In several parts of India, especially in its forested tracts, tribals and others have traditionally survived on forest fauna and flora during periods of climatic stress. It is said the tribals of Chotanagpur plateau can survive where even rats would die. But with trees having gone, the survival foods have also disappeared. From Udaipur to Sarguja, the bottom of the survival pot has fallen out for these tribals.

In Sarguja district of Madhya Pradesh, food shortages have sent tribals hunting for even cats and monkeys. During the day, villages got deserted while their inhabitants roamed in the jungles in a desperate search for fruits and roots.

To earn an immediate income, desperate tribals have to forsake their future. An estimated two million to three million of the country's poorest people, mostly tribals, survive on headloading -- cutting wood from state forests and selling them in small towns -- even in normal times. Whenever drought strikes, lakhs more join the normal headloaders. This can, however, be prevented if relief comes early. "In fact, at such a time, millions can be employed to plant trees," says environmentalist Kishore Saint from Udaipur. But in Udaipur, thousands were forced to cut trees as no relief has come (See box: Selling trees for rotis).

Kerala's problem, however, is different. While this two-monsoon state received good rains during the 1991 summer monsoon, the winter monsoon was 25 per cent below average.

Kerala's topography is unique. Within a width of some 60 km, on average, the land falls rapidly from 1,066 metres high in the Western Ghats to the Arabian Sea. The 41 east-flowing rivers are therefore very short (less than 100 km in length). Rainwater runs off from the highest slopes to the estuaries within 48 hours. Of the total annual rainfall of over 3,200 mm, about 20 per cent falls during October to December. This year, these short rivers went dry very quickly, especially in the upper reaches.

Vegetation plays an important role in regulating the water balance of the region. But the greenery of Kerala is deceptive. When there were thick forests in the state -- 45 per cent to 55 per cent of the geographical area in 1947 -- a substantial portion of the rain water would percolate underground and recharge drinking water wells, before the rivers ran into the sea. Kerala has the highest density of dug wells in the world.

Forests have now declined to 20 per cent. This has reduced recharge of groundwater. Also, when forests are cleared for plantations, the vegetation on the ground is removed, increasing runoff and soil erosion, thus hindering percolation of water. Storage reservoirs built on the rivers also retain and divert the water, curtailing groundwater recharge further. Low groundwater levels bring salt water from the sea into the water table and contaminate drinking water sources.

Following the severe drought of 1983, tubewells have been installed in large numbers. Irrigation minister K M Jacob said in 1992 also, "A decision has been taken to sink more tubewells in order to tide over the present drinking water crisis."

Pollution too plays its role in exacerbating the water crisis. The people of Kuttanad are dependent on water from canals and backwaters crisscrossing the area. The Thanneermukkom salt water barrier checks the ingress of saline water and maintains water levels in paddy fields. This year, as small farmers failed to harvest their crops in time, the opening of the barrier was delayed. And pollution caused by unlimited use of chemicals and pesticides in the paddy fields rendered water in the canals unfit for drinking.

Barren pastures

The 1992 drought has shown that the coping mechanisms used in the past are falling apart. The National Calamity Fund, set up on the recommendation of the Ninth Finance Commission, provides fixed amounts for relief expenditure, regardless of the level of distress, leaving states cash-strapped this year. The states too have failed to develop comprehensive land and water management systems. Their development interventions have upset the ecological balance which now shows up with fury when the rainfall dips.

In the last two decades, various measures have been taken by the government during droughts to provide employment and foodgrains to drought-affected people. But little attention was paid to the needs of their animals.

"Fodder," says C H Hanumantha Rao, an eminent agricultural economist, "is a major missing link in our agricultural policy." Fodder shortages were responsible for considerable hardship in western India during the 1987 drought. This year again, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Maharashtra have not been able to solve the problem of fodder production and distribution. Grass productivity in most grasslands is less than a fifth of their natural levels.

A Crisis Management Group (CMG) had attempted to set norms for a relief plan after the 1987 drought. "In July 1987, states were asked to prepare contingency plans for fodder banks and cattle camps," says S V Giri, who headed the CMG. The creation of the calamity fund should have helped evolve a good management strategy.

But organised fodder distribution continues to be ad hoc and inadequate. "We usually do not undertake fodder distribution, owing to its bulk, carriage and transportation. Instead we disburse money and let people organise its procurement," says Mitha Lal Mehta, agriculture secretary, Rajasthan.

Says Binoy Acharya of Unnati, an NGO in Ahmednagar, "Fodder is available at Rs 6 per kg in Gujarat. Out of this Rs 4 is given by the government as subsidy and the balance it wants NGOs to raise from industrial houses. But no industry has come forward so far." When money is short, governments take mindless decisions. No fodder is given to sheep and goats, "as these are considered unimportant animals". The Un Utapadak Sangh of Kutch has filed a case in the high court against this policy, due to which 3,000 sheep and goats have perished in Kutch alone.

"It is a shame," says Kishore Saint, "that we have still not learnt our lessons". Like Saint, Anna Hazare and numerous other environmentalists have worked during the 1980s to improve the ecology of villages through people's involvement. The results in most cases have been rewarding (See box: Green and surviving). "But policies to get such participatory models of rural development going are still missing," says Saint.

Dry wells

Shortage of drinking water also raises serious questions about water management. The 1991 report of the Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission claims that only 3,326 problem villages remain to be covered in the year 1992-93. And yet a large number of villages are facing a drinking water crisis this summer.

Maharashtra is an excellent example. The state government claims 25,000 villages have acute drinking water problems. But the mission says all but 50 villages have been provided with drinking water sources.

Says S K Biswas, a senior officer at the mission, "When one says that so many villages have been covered, one is not taking into account villages that have relapsed into a no-water status because of wells drying up or handpumps not working. A survey of such villages is on and is expected to be completed by the end of next month."

Some 85 per cent of the country's rural water supply comes from groundwater. Actual groundwater consumption is usually six per cent to 10 per cent of its potential. But in some areas, the groundwater exploitation rate is 75 per cent to 180 per cent of the potential. In Mehsana district, the groundwater potential is being utilised at the rate of nearly 175 per cent.

Groundwater exploitation is particularly heavy in the dry regions of India. In Maharashtra, for instance, nearly one- quarter of all blocks are dark or grey, where further groundwater development ought to be restricted because of the high rate of existing exploitation.

But there is an increasing demand for agricultural and industrial purposes in such areas, and water as a natural resource is slowly going beyond the reach of the poor, says Biswas.

The need for good land and water management is obvious. Without this no place in India can escape the menace of drought. As things stand even Cherrapunji -- the world's wettest place on earth -- which has been badly deforested, faces drinking water shortages.

Related Content

- The role of waterways in promoting urban resilience: the case of Kochi city

- The challenge of agricultural pollution: evidence from China, Vietnam, and the Philippines

- Budget 2013-2014: speech of P. Chidambaram, Minister of Finance

- Of soils, subsidies and survival: a report on living soils

- Ecology and geography of plague transmission areas in northeastern Brazil

- Old industry, very slow change