Technology gives traditional water mills a lift

THE traditional gharat (water wheel) has caught the technologist's eye and deceptively simple modifications to its design have made it at least 40 per cent more efficient and also enlarged its capability so that it can power several machines simultaneously.

THE traditional gharat (water wheel) has caught the technologist's eye and deceptively simple modifications to its design have made it at least 40 per cent more efficient and also enlarged its capability so that it can power several machines simultaneously.

The gharat, in use for centuries in the Himalayan region, can be developed into an excellent alternate energy source for far-flung, hill villages. Even today, Chamba district commissioner S Pidke explained, "except in the plains areas, gharats are found in almost all areas of Himachal Pradesh."

Taking off from this traditional method of exploiting running water as a renewable energy source, agencies such as Himurja in Himachal Pradesh, Agro Engineering Corporation of Arunachal Pradesh and Institute Technologique in Dello, Nepal, have used the gharat principle to develop innovative single and multimachine designs.

Shimla-based Himurja's new designs are 40 to 50 per cent more energy efficient than traditional gharats. Positioned under a 10 m waterfall, the Himurja design has a capacity of 10 hp or 7,500 watts. While the traditional system was used only for powering mills, the modified multimachine version can be used to run oil expellers and for flour mills and rice husking, wood cutting, cotton landing and wool weaving machines, either singly or severally and also simultaneously. Small quantities of electricity, sufficient for a few rural households, can also be generated through improved water mills.

Surjan Singh, an enterprising machine-shop owner, has installed several multimachine gharats in Chamba and neighbouring districts and has ventured even as far as Bosoli, in Jammu & Kashmir. In Holi, some 80 km from Chamba a typical Surjan Singh multimachine gharat successfully operates a wheat mill, a saw mill and a loom (wool-weaving machine) simultaneously. And in Andral, another village in Chamba, a cluster of commercially run gharats is proving to be a profitable venture. In the Bondilla, Kalaktung and Thimbu areas of Arunachal Pradesh, too, similar multimachine gharats are working efficiently.

Traditional watermills, made by village carpenters and blacksmiths from locally available materials, consist of a wooden turbine and wooden or iron blades that rotate when water flows over it. A shaft connects the wheel to a rotating stone, which moves against a stationary grinding stone. Water from a stream is diverted through an open wooden channel to fall from a height of about 8 metres on to the turbine, thereby activating the system. In order to stop the machine, the gharati (operator) just changes the direction in which the water flows on to the blades.

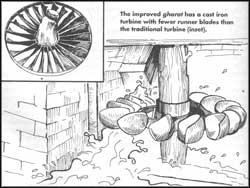

In the improved gharat, the traditional wooden turbine has been replaced by a cast iron one and has fewer runner blades -- no more than 18 as compared to 28 in traditional gharats. The blades have holes at the periphery to ensure an even flow of water and smooth movement of the turbine. The traditional gharat's stone bearings have been replaced by cast iron and mild steel bearings, thereby increasing the number of revolutions per minute.

Traditional watermills are still being used in the hill areas, but in some places they are giving way to electric atta chakkis (flour mills). In the plains areas of Chamba district, where gharats were once common, their decline is appreciable. All the villages in the district are electrified and electric atta chakkis are gaining in popularity.

Originally, gharats were owned and operated by gharatis, for whom this was a family tradition. They were paid in kind, usually a kilogram of grain for every 15 kg of grain ground. In Chamba, however, gharatis are now opting for other professions because of meagre earnings and because of fierce competition from more conveniently located, electric atta chakkis.

The modified versions are more efficient, but they face an uphill task in gaining acceptance, especially in the more remote regions, because some of the parts have to be brought in from faraway towns. The multimachine gharat could perhaps compete commercially with electrically run machines, but the government is doing little to popularise this technology and the task has been left to local entrepreneurs.

They are being marketed by Himurja through the Khadi and Village Commission, with project officers stationed in each district, but poor advertising of the improved models, which cost about Rs 12,000 each, is responsible for poor sales of improved gharats. For example, Balaram Mahajan, a gharati from Dulara, bought an inferior turbine from a local shop and paid a high price because he was not aware that the subsidised price was Rs 500.

This versatile technology has considerable potential in other hilly areas as well, according to Gopinath Padhi, chief engineer of the Suvarnarekha Irrigation Project. "The watermill," he said, "could function in some areas of the Similipal hill range in Orissa." This is equally true also of other hilly regions with water sources, even streams, as can be found in Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and in the north-eastern states.

---Mrinal Chatterjee is a journalist who prepared a report on watermills as part of a journalists' fellowship programme sponsored by the Centre for Science and Environment.